Mr. Anderson tells us that he had gotten off of the bus and had walked toward the shopping center and felt he needed to rest. He had picked this spot because it was cooler in the shade. He also tells us that is is fine and definitely does not need an ambulance to go to the hospital.

Mr. Anderson is conscious, alert and oriented to time, place and purpose. He denies any medical issue and the desire for treatment transport. He appears to be able to care for himself and has a method to communicate with someone, should his condition change.

This works for us. We cancel the ambulance as it pulls up to the curb, wish Mr. Anderson a good afternoon and return to the station. Pasta with a special marinara - al fredo sauce, a Caesar's salad and garlic bread await us back in the barn.

The evening passes at the station. Dinner, the daily paperwork and a false alarm fill the early hours; the news and some e-mails finish it off.

At thirty minutes past midnight, a computer generated voice tells me I am going to a medical aid. The station alert light casts enough of a red glow in my dorm, so that I don't trip over anything on my way out. We are being dispatched to a reported man down, at the same location where we met Mr. Anderson seven hours before.

We discuss the possibility of this call being related to the one earlier and agree that it could be. Two minutes later, we get canceled. Dispatch tells us that the RP (reporting party) has called back and doesn't need an ambulance.

We discuss the possibility of this call being related to the one earlier and agree that it could be. Two minutes later, we get canceled. Dispatch tells us that the RP (reporting party) has called back and doesn't need an ambulance.As we pull around the corner, we see Mr. Anderson seated in the parkway, talking on his cell phone. The street is nearly empty now, as all of the local businesses have been closed for several hours.

I hop off of the engine as it comes to a stop; Mr. Anderson is intently speaking into the phone. "Who are you talking to?" I ask him.

Without saying a word he hands me the phone. I take it and ask who it is. It is one of our dispatchers, a 911 call taker. She tells me that Mr. Anderson had called a third time and said that he needed a deputy because he was disoriented, but he didn't need an ambulance. I tell her that I will advise the fire dispatcher by radio if we need a deputy.

I hand the cell phone back to Mr. Anderson and note that his shoes are several feet away, his backpack is open, its contents spilling onto the grass. His wallet is on the ground as well, a few credit cards laying next to it. We also find a business card from a charitable organization with his name printed on it.

Mr. Anderson is even more pleasant than he was earlier. He still is trying to tell us that he doesn't want an ambulance or need to go to the hospital. I make up my mind that Mr. Anderson isn't staying here. I don't yet know whether we're going to take him, or if I'm going to have to convince a deputy to take him home. Frankly, I didn't think about checking his cell phone for contact numbers until later.

I begin the series of questions to determine whether he is mentally oriented. He knows where he is more or less, he knows his name and his address. He isn't too sure of the time, but then, neither am I. He knows what he was doing when he arrived at his current location and he knows who the current president is. We determine that he does not have any recollection of our earlier conversation.

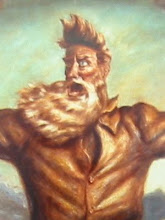

"Mr. Anderson. You don't remember talking with me earlier this evening?" Mr. Anderson shakes his head no. I am shocked. I have a distinctive look. Kind of like Bigfoot has a distinctive look. Or Chupacabre. Only not as cute nor as charming. People always remember my face, it is etched into their memory like a bad root canal procedure. They try to forget, but can't.

The fact that Mr. Anderson does not remember us being there talking to him is enough for the two medics on my crew that evening to consider Mr. Anderson in a slightly altered mental state. Enough so that we can treat him, even if he really doesn't want it.

I request the ambulance to respond again. Vitals, an assessment and BGM reveal a hypertensive diabetic with a blood glucose level in the low 60's. Not critically low, but low enough to cause a problem. We give Mr. Anderson some oral glucose, a sickeningly sweet concoction that provides a quick blood sugar boost.

The ambulance arrives and we load Mr. Anderson into the back of the ambulance. The sugar seems to help Mr. Anderson a little, but some of his answers still seem a little off.

The boot and I are having a conversation at the back of the ambulance as the ambu crew sets Mr. Anderson up for the ride. Somehow he misinterprets what we are saying and thinks that we are going to leave him there. A look of genuine fear flashes across his face. I am startled by this look of fear and we instantly assure him that we are not leaving him. He accepts our assurance and relaxes as the paramedic student begins an IV on him.

We double check the grassy parkway for any of Mr. Anderson's belongings that we might have missed. Finding none, we send the ambulance on it's way.

On the way back to the station, we talk about Mr. Anderson's plight. Of course we second guess ourselves about not being a little more assertive the first time we rolled on him. I am not sure what conclusions the other members of my crew came to, but I believe that we were within policy and that we met our moral obligation when we determined that he was in no danger and respected his wishes to be left alone.

Two shifts have passed since this call. We have driven by Mr. Anderson's resting spot several times, as it is near where we shop for chow. Each time I have looked for him and have been relieved not to see him.

I don't think he is homeless, I do think that he may be suffering from the early stages of some form of geriatric dementia. The low blood sugar didn't help matters either. Hopefully he has someone to look after him, so he doesn't have to run into the likes of us again.

Thanks for reading,

Another Joe, keeping the wolves from the door.

This fire also served as an evaluation tool for me. My junior rookie was had been on about 7 months. This was the first time I got to see her actually fight fire. She performed well and I was

This fire also served as an evaluation tool for me. My junior rookie was had been on about 7 months. This was the first time I got to see her actually fight fire. She performed well and I was